[note: the following is a more “scholarly” reflection, representative of some of my ongoing doctoral studies which focus on making sure that families working through the challenges of raising children previously abused or neglected, or are having attachment issues find a welcoming place of worship in their community… a place at the table, if you will. If you are interested in following some of my more scholarly work, check out www.fullhousewithaces.com )

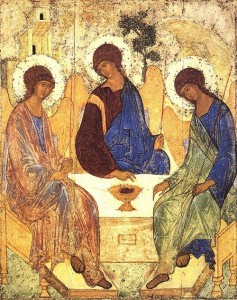

“Trinity,” a work of art attributed to Russian painter Andrei Rublev, was created in the 15th century. It is Rublev’s most famous work and depicts the three angels that visited Abraham at the Oak of Mamre (the story can be found in Genesis 18:1-15). The symbolism is purposefully multifaceted, and therefore the work is understood to be an icon of the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The three figures, depicted as angelic visitors, are seated at a table. They are beckoning the view to join in the meal, to sit at the table.

“Trinity,” a work of art attributed to Russian painter Andrei Rublev, was created in the 15th century. It is Rublev’s most famous work and depicts the three angels that visited Abraham at the Oak of Mamre (the story can be found in Genesis 18:1-15). The symbolism is purposefully multifaceted, and therefore the work is understood to be an icon of the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The three figures, depicted as angelic visitors, are seated at a table. They are beckoning the view to join in the meal, to sit at the table.

The personal, relational nature of God as plurality in unity—three-in-Oneness—is the basis for meaningful engagement between all persons. How can I make such a claim? In part, because of my Christian belief is that humankind is created in God’s image:

So God created mankind in his own image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them. (Genesis 1:27, NIV)

Because God is relational, existing in three coequal persons in a mysterious diversity while maintaining essential unity, we are relational. We reflect the nature of God: we are created for relationship. These relationships should include the same diversity that exists in the Godhead—extending ourselves to reach out to those unlike ourselves in some way. We need to be cross-cultural.

When it comes to cross-cultural engagement, however, we need to be careful about HOW we are in relationship with the “other”—whether that “other” is the opposite gender, someone of another race, or any number of distinctive characteristics that could be used to keep us separate, divided, and suspicious of one another. Cultural engagement, the stated topic of the doctoral work for which I am currently engaged with a small cohort of students at Multnomah University, involves a purposeful process of humbling approaching the “other” in our midst, all the while mindful of the baggage we come into these interactions with.

As a white, middle class male, the baggage I need to claim is that I have always lived in a situation where I was part of the dominant class. Whether consciously or not, I can enter a cross-cultural interaction with assumptions that I bring the expertise and relational capital. I can expect accommodations be made for me, often not mindful of the sacrifices others might be making to cross cultural boundaries to help me feel comfortable. Giving so little and expecting so much in return makes it hard to set the stage for true hospitality. This must change if there is going to be meaningful cultural engagement and reconciliation. So, we start where we began… back to Rublev’s Trinity.

Just as the icon suggests, a helpful image of coming together for cultural engagement can be sitting down at a table together for a shared meal. This concept of the open table was the topic of significant discussion during my recent studies at Multnomah University.

Significant issues were raised in this discussion, such as: What are the roles played at the table and who does the inviting? Who sits at the head of the table and determines what each one can bring to the meal? And, most importantly… who has built the table and set it in its place? What the dominant class often fails to see is that many choices are made prior to the gathering for the meal at this supposed “open table,” decisions that reflect the power structures that favor the perpetuation of class distinction and cultural enmity.

Why even bring these issues up? Well, our diverse group includes a number of those not in the majority, and they cannot assume that they will be heard will in the midst of those who are part of the dominant social group. We spoke of the necessity to be intentional about self-examination, asking ourselves if we are engaging the “other” on our terms, from a place where we comfortable. Or, are we intentionally inconveniencing ourselves in order to give the “other” room to speak into our lives. Are we worried about our place in the pecking order, afraid of losing a position or influence within the conversation, or are we open to assume the role of the least, the lowly, and the servant? (Luke 22:24-27 would be a good passage to read before we gather with any group of diverse people, eager to determine our place among those who gather).

Why even bring these issues up? Well, our diverse group includes a number of those not in the majority, and they cannot assume that they will be heard will in the midst of those who are part of the dominant social group. We spoke of the necessity to be intentional about self-examination, asking ourselves if we are engaging the “other” on our terms, from a place where we comfortable. Or, are we intentionally inconveniencing ourselves in order to give the “other” room to speak into our lives. Are we worried about our place in the pecking order, afraid of losing a position or influence within the conversation, or are we open to assume the role of the least, the lowly, and the servant? (Luke 22:24-27 would be a good passage to read before we gather with any group of diverse people, eager to determine our place among those who gather).

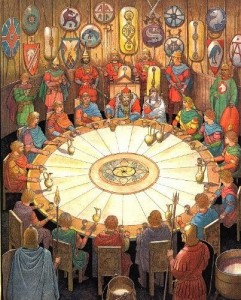

As I thought about the concept of the “open table” and the struggle to determine the place of each person in a diverse group, the image of King Arthur and the Round Table came to mind. According to legend, the significance of the Round Table was that no one person, not even King Arthur, would be able to sit at the head of such a table. A round table enforced the concept of equality—equality in status, the ability of all seated to speak and influence the group, and shared decision-making within the group.

Perhaps with the imagery from the stories of Jesus in gospels in mind (see Luke 22:24-27 yet again), the legend states that King Arthur ordered the Round Table to be built in order to resolve a conflict among his knights concerning who should have precedence. The Round Table was therefore built to ensure that all the Knights of the Round Table were deemed equal and each of the seats at the Round Table were highly favored places. Apparently, each knight had to make the same pledge: “In serving one another, we become free.”

To be invited to the table with the Triune God, and invited to join in relationship with the divine, is an honor and a privilege. We are ALL invited, and we share God’s special favor. Who are we, then, to assume any status other than that which God has already given us? Let us set aside the class distinctions and cultural imperatives that reinforce the separation between those whom God has called brothers and sisters. Cultural engagement as equals at the open table of our Lord and Savior is worth whatever sacrifice we feel we might need to make.

Click here to subscribe to our RSS feed with your favorite email client and be alerted to new articles.

Click here to subscribe to our RSS feed with your favorite email client and be alerted to new articles.